Update: How you teach ‘Consent’

Looking beyond the individual

By Tasha Mansley, Education and Programmes Manager at Split Banana

Talking about “consent” in many schools has turned into a bit of a tick box exercise, and after yet another assembly on the topic, students are left rolling their eyes. Why then, are there still such high rates of sexual and gender based violence in UK schools (Gov, 2023)?

As with many old school approaches to RSE, the default has often been to focus on policing individual behaviour, with a lack of awareness of how these behaviours are produced by a wider culture (Setty, Ringrose and Hunt, 2024). It’s helpful to recognise that there will be a culture of consent modelled within the school, but also that we are influenced by the norms surrounding gender and sexuality beyond the school gates, which teachers have some power to challenge, by unpacking these with students in the classroom.

In our bespoke training for schools on this topic, we introduce this model, showing how the social norms trickle down to impact institutions, relationships and individuals. Change can also trickle out from different points on this map. Let’s look one at a time about how these relate to ‘consent’ and how you can shift your pedagogy and policies to influence positive change.

Cultural: Creating spaces to think critically about gender & sexual norms

Despite what the proposed amendments to the government guidance for RSHE might imply, opening dialogue about gender as a social construct can help us to challenge the pressures and expectations that come from gender norms, including those that lead to sexual and gender based violence.

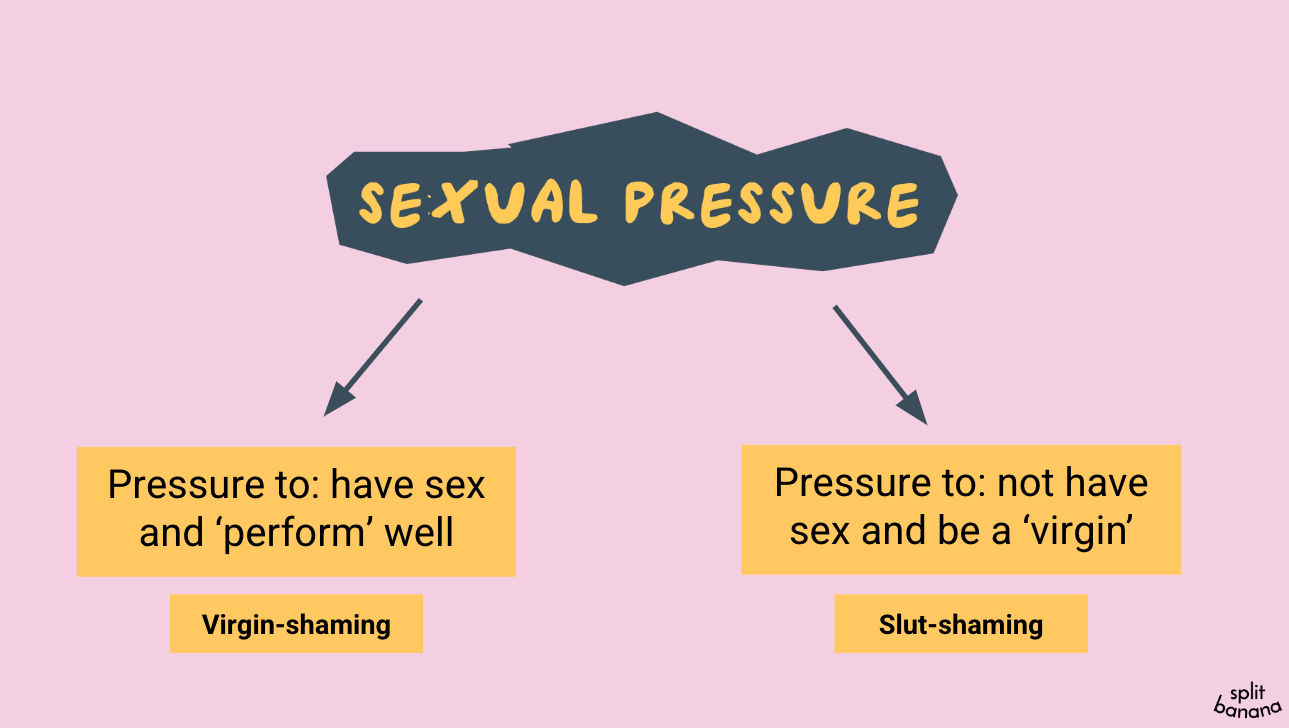

A common example that comes up in RSHE, is the binary heterosexist script that boys need to ‘get’ and ‘ask’ for consent, and girls either ‘give’ or ‘say no’. These come from wider cultural assumptions that boys are innately ‘up for sex’ and girls are responsible for ‘gatekeeping’ their ‘virginity’. However this can put pressure on both sides, for example boys feeling like they ‘should’ go along with whatever a girl wants, even if they’re not into it, or girls being shamed for being too sexually promiscuous.

Some useful ideas to explore with your students might be:

What are the histories of these narratives? (e.g. ideas of women have a ‘value’ based on their sexual purity)

When did we first encounter them? (e.g. jokes, song lyrics, comments “boys will be boys”)

What other aspects of our identities do these pressures intersect with? (e.g. do they change based on race, religion, sexuality, age?)

What impact do these ideas have on how people think they should behave and what they might consent to?

By unpacking these very real, fatalistic and highly gendered social pressures, we can support young people to resist them, and as a next step, have an open dialogue about what narratives and norms they want to exist among their peers instead.

Institutional: Bringing trauma informed practice to a whole school approach

What does your school culture model to your students about consent?

A third of the girls surveyed by EVAW (2023) said they didn’t think school would take them seriously if they reported sexual harassment, and that 60% had heard sexist language from teachers. Victim-blaming language (which you can read more about here) plays a big part in this, and can also lead to diminished or inadequate safeguarding responses. Victim blaming messaging can also be carried implicitly, if our lessons focus only on how to ‘keep yourself safe’ or ‘how to say no’, and not enough on the social and relational aspects of consent.

Consider:

Who are your ‘lessons’ and ‘messages’ about consent addressing? Who is not included? What generalisations are being made?

What steps does a young person have to take in your school to talk about a breach of consent? How are they received if they do? Does this change depend on their age, race, sexuality, gender, personality?

Have you spoken to the young people in your school about your sexual harassment policies? How much agency do they have in shaping the school’s culture?

Within lessons, it is important not to make assumptions about what experiences students may have experienced or witnessed when teaching about consent and that it may be a triggering topic.

Being mindful of this, might look like:

Giving a clear outline of what will be covered before the start of the session.

Never picking on individual people to give responses.

Allowing students the freedom to not participate in activities or take time out if needed.

Beginning and ending a session with a creative, calming activity.

Always providing accessible signposting to services that can support young people if they don’t want to speak to an adult in school. Check the NHS’s signposting for services that offer support after rape and sexual assault and this animation showing what Sexual Assault Referral Center (SARCS) are like. We update our signposting for young people on this topic here.

Relational: Opportunities to imagine and practice positive communication skills

We teach that “Consent happens when all people involved in an activity agree to take part by choice and have both the freedom and capacity to make that choice” - but what are some of the relational factors that might impact someone’s freedom to give an honest response?

Worrying about offending the other person, or the consequences of rejecting them - yes because “I don’t want to hurt their feelings”

Wanting to please the other person or belief the other person’s pleasure is more important than their own - yes because “it’s what they want”

Investment in the relationship - yes because “I want them to keep going out with me”

Perceived sexual norms and expectations within the wider peer group - yes because “it’ll be seen as weird if I don’t”

Past experiences of boundaries not being respected - “yes because they won’t listen”

These relational experiences are impacted by the intersectional and internalised power structures of wider society, impacting our beliefs around what is expected of us and what we are entitled to.

The nuance of this reality is important to acknowledge if we are to take meaningful steps in consent education. In my experience, young people are worried about this relational aspect the most, the most frequently asked questions are:

How do you reject someone nicely?

Won’t checking in just ‘kill the mood’?

What if later someone says they didn’t actually consent?

These are important and legitimate worries, and I think shows how young people want to learn communication tools that feel authentic and relevant. There’s no one-size-fits-all script here, so this is an opportunity to allow them to come up with their own answers.

You can do this through using creative pedagogies and distancing techniques, for example storyboarding interactions between two characters, with different verbal and non-verbal ways they might communicate their desires and boundaries. Outside of RSHE, you could engage critically with literature, music and films, analysing examples of consent and boundaries being communicated, or what the barriers are to this from the different character’s perspectives. These don’t necessarily have to be romantic or sexual relationships, use friendships as examples too.

Individual: Supporting young people to developing a sense of comfortable boundaries

Finally, we can also work on an individual level, supporting young people from an early age to build their own embodied awareness of what feels comfortable or uncomfortable, and to practise communicating that. This isn’t to forget the impact of all the other layers above, but to help young people reconnect with their intuitive personal sense of what feels ok (or not) for them.

For example, in this traffic light game, we read out and show different every-day scenarios (e.g. a friend asking to borrow your pencil case, a young family member asking to sit on your lap when you’re watching TV) and ask students to feel their gut reaction and indicate if they feel a yes (thumbs up), no (hands in an X) or a maybe (shrug). Even this simple practice, can start building an awareness that we all have boundaries, and not everyone’s are the same.

The challenge of teaching this in schools, is that schools themselves are often quite uncomfortable spaces! Students often learn they can’t go to the loo when they need to, or have to sit next to people they don’t want to. Be prepared for this to come up, once you begin this work!

Summarising the steps you can take:

So… it’s time to go beyond a ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ approach to consent. It is a baseline minimum that young people leave school knowing the law around consent, but what I find they really want to know, is how to navigate the nuances of understanding and communicating their desires, in a world filled with mixed signals, sexist sexual scripts and social pressure. To support them, RSHE has to take a multi-layered approach.

In your school you can begin by:

Opening critical dialogue around gender/sexual norms and how these impact expectations and behaviours surrounding sex and relationships.

Challenging the way these norms are perpetuated through school policy, teacher language and safeguarding procedures.

Supporting young people to imagine and practice positive and honest verbal and non-verbal communication that feels authentic to them.

Creating opportunities for young people to develop self awareness around their desires and boundaries, and a respect for the boundaries of others.

If you have comments or questions about this blog, please contact me at tasha@splitbanana.co.uk or via LinkedIn.

Working with us:

You can book bespoke training with us for next academic year (2024/25), get in touch with hello@splitbanana.co.uk to start a conversation. Keep an eye on our store for public training around this topic.

We have differentiated workshops exploring this topic for different ages, that can be built into a spiral curriculum:

For years 8-10 we recommend booking:

Boundaries

Consent

For Years 11-13 we recommend booking:

Intimate Relationships

Culture of Consent

Further reading:

For kids: Let's Talk About Body Boundaries, Consent and Respect - Sarah Jennings

For teens: Can We Talk About Consent - Justin Hancock

For adults: Tomorrow Sex will be Good Again - Katherine Angel

Further watching:

How to Say No Clearly and Kindly - Nicola Willians.

Why We Need to Change the Way Young Men Think About Consent - Nathaniel Cole.

Consent and Relationships Today - Dr. Emily Setty.

Instagram accounts to follow: